ON JUNE 24, 1968, Joe Franklin interviewed a fabled but by then obscure cult singer on his WOR radio show. Lee Wiley had declared her retirement a decade earlier from an erratic career that began in the Depression. “People are calling up all the time and asking me if I want to work,” claimed the once-influential jazz stylist. “I say no, I don’t. Why? I’m very happily married.” But even in her ‘30s and ‘40s heyday, Wiley had been “a very elusive person,” according to a fan and friend, singer-pianist Charlie Cochran. “There were very few photographs of her in the paper. There was very little written about her. Nobody but the intelligentsia of jazz knew who she was.”

Yet Wiley – like Mildred Bailey, Connee Boswell, and Bing Crosby – was a pioneer jazz vocalist, and a white artist embraced by both black and white players. Her singing was unmistakable. The Oklahoma-born songbird had a languid, husky sound with a Midwestern drawl; people compared it to honeysuckle and Southern Comfort. Her time was relaxed, her improvising minimal; the smile in her voice masked all autobiography. What she lacked in brains she made up for in taste. Between 1939 and 1943 – long before the Ella Fitzgerald Song Books – Wiley made a classy series of 78-rpm albums in tribute to Porter, Arlen, the Gershwins, and Rodgers & Hart. Some of the best jazzmen of the day backed her. She was a well-known fashion plate. But Ted Ono, whose Tono label has reissued most of her early work, described Wiley as a diva – “selfish, impatient, and short-tempered,” to the detriment of her career. She drank like a fish, cussed like a sailor, could treat musicians abusively, and had no qualms about stealing married men – including the star trumpeter and bandleader Bunny Berigan, with whom she recorded. “They had a pretty torrid affair,” says Dan Morgenstern, the celebrated jazz historian. “Bunny’s wife hated her.” But Wiley got away with a lot, for she was a dish, with smoldering sex appeal and dark hair that tumbled past her shoulders.

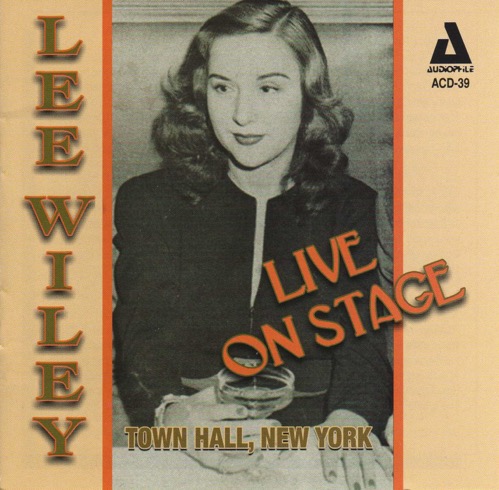

That was the woman jazz fans saw at New York’s Town Hall and Ritz Theatre in 1944 and 1945. Wiley appeared there as a frequent guest in a historic set of jazz broadcasts commandeered by Eddie Condon, the guitarist and concert promoter. This CD gathers Wiley’s songs in one definitive collection.

Born October 9, 1908, Lee Willey (as her name was initially spelled) sprang from partly Cherokee roots in the hick town of Fort Gibson – “about as small as you can get,” she told Franklin. But she had big dreams: “When I was a little girl, I used to sit in the back of my class and dream of being a great singer.” In her early teens, she and a boyfriend went to shops “in the colored part of town” to hear race recordings by Bessie Smith, Clara Smith, and her favorite, Ethel Waters. “My mother didn’t like me going down there,” Wiley told Franklin. But the ambitious teenager scored a job on Tulsa radio, singing and playing piano after school. At fifteen, she said, “I just ran away.”

Wiley sang her way from St. Louis to Chicago to New York. There, things happened fast. In 1931 she became a regular on the radio series of Leo Reisman, a society bandleader. Her come-hither sound proved highly enticing on the air, and soon she took over Reisman’s show. In 1933 she began a relationship – both romantic and professional – with Victor Young, a radio conductor and the composer of such standards as “Street of Dreams” and “(I Don’t Stand a) Ghost of a Chance (with You).” A year later, Wiley graduated to radio’s prestigious Kraft Music Hall, where she acted on playlets that led into songs. In a fit of pique, she stormed off the show – a typical move for a singer whose temperament would cost her many opportunities. One of these was a lead in the 1933 revue Strike Me Pink. “The producer said something terrible to me,” she informed Franklin, “so I just grabbed my Russian sables and stalked across the stage. I was living on the thirty-fourth floor of the Pierre Hotel, so it didn’t bother me.”

Clearly, she liked putting on airs. “All my clothes were made especially by Madame Du Forswell at Bergdorf’s,” she explained. Wiley boasted of having worked in “the greatest nightclub that New York ever had,” Fefe’s Monte Carlo at 40 East 54th Street. “It was for people that had millions,” noted Wiley. “Opening night I had this long white ermine coat and I had orchids ranging clear to the bottom, right straight down.”

But she took her singing as seriously as her clothes. Wiley recalled some advice from the Metropolitan Opera tenor James Melton, whom she met at NBC: “He said, ‘You know, you have a good voice, but you’ve got to go and learn to sing. So I started studying. I was going to Carnegie Hall every day.” Still, she sounded utterly natural. Saxophonist Bud Freeman told her that her sweet, lyrical quality reminded him of Bix Beiderbecke, the pivotal ‘20s cornetist. Gentle improvisations flowed out of her like ripples on a brook. Wiley had charming stylistic trademarks. She ended phrases with a lazy falling vibrato, and often trimmed them with a “mordent” – a little grace note – that evoked a flirty wink. She rarely probed into words; instead she maintained the vacant charm of a boozy Southern belle. “It’s refreshing, in a way, that it’s like that,” says Charlie Cochran. “The thing I liked was her vagueness, her pauses – not being quite all there.” Certainly she saw little to analyze in her style. “I had good training,” she told the author and radio host Richard Lamparski in 1972. “You learned to breathe, and that’s about all there is to singing other than what you do with your mind, you know.”

Wiley was beloved by Eddie Condon, the Indiana-born guitar player who in the 1920s had helped found the so-called Chicago jazz sound. In 1928 he moved to New York, where he became a fixture on 52nd Street and in prominent swing bands, notably Artie Shaw’s. Condon spent much of the ‘40s waging what critic Leonard Feather called “a one-man crusade for jazz,” with an emphasis on Dixieland. He became a concert promoter and Greenwich Village club owner; he published a memoir in 1947 and hosted the first jazz TV show the next year. His Town Hall and Ritz Theater broadcasts achieved special renown. Condon showcased a galaxy of swing, Dixieland, and Chicago jazz stars, including James P. Johnson, Willie “The Lion” Smith, Sidney Bechet, Muggsy Spanier, Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, Bobby Hackett, and Hot Lips Page. Wiley, says Dan Morgenstern, “was the only singer associated with those concerts on a regular basis.”

In them she drew heavily upon her songbook repertoire, and added songs by Vernon Duke, Dorothy Fields, Eubie Blake, Victor Young, and Willard Robison, the Missouri-born author of rural, melancholic story-songs. Wiley liked to tell them simply, and she insisted on spare backing from jazz stars who normally blew full-out. The accompaniment on “Don’t Blame Me” – which includes a restrained trombone solo by Tommy Dorsey – is as light and airy as a cloud. In “Down with Love,” trumpeter Billy Butterfield answers her phrases with delicate, playful embroideries that never got in her way. The band heats up for “On the Sunny Side of the Street,” and Wiley stretches out with some frisky improvisations, while never losing her breezy lilt. On Cole Porter’s “Why Shouldn’t I?” she and a trio led by her frequent cohort, pianist Joe Bushkin, achieve a café-style intimacy. “I Can’t Get Started” teams her with pianist Jess Stacy, her husband for five stormy years. Even with his aggressive swing playing, her singing is a model of relaxation. Once in a while, as in “Someone to Watch Over Me,” the words penetrate her genial haze, turning her noticeably wistful.

By the ‘50s, Condon’s series had ended, and Wiley faded from view. The once hot-to-trot girl about town now lived with her mother in a small apartment on Manhattan’s East Side. Admiring producers at Columbia, Storyville, and RCA recorded her impeccably, but except for one last club appearance at Mister Kelly’s in Chicago, Wiley didn’t perform. The husband she mentioned to Joe Franklin was mysterious. “She called him ‘my fella,” said Cochran. “I don’t know who he was. He must have kept her, basically. She was never married to him when I knew her.” Cochran, who adored her singing, had finagled a friendship with her in 1955, when he was eighteen. For the next few years he took her on numerous “rampages around town” to jazz clubs and cabarets. “She would sing at the drop of a hat,” he says. “Not one, but five or six songs. She loved sitting in. Which was odd for somebody who didn’t want to work in a club. She would stand with her hands by her side. The eyes became slits. And this sound would emanate from her that was just gorgeous. She had a weird kind of charisma – a little spooky.” He was certainly jarred when she saw she had a finger missing – the result of “some sort of fight, a drinking accident. She could be violent and throw lamps and ashtrays and stuff like that. Ruby Braff told me you had to duck sometimes. She had very good aim.”

Wiley claimed she didn’t miss the spotlight, yet she boasted for years of the 1963 teleplay Something About Lee Wiley, which starred Piper Laurie in a true account of a horse-riding accent that had partly blinded Wiley in the ‘20s. Bitterness infused her comments on the “noise” that now passed for singing. “I think show business today is kind of laughable,” said Wiley in 1968. She spoke well of Tony Bennett, Frank Sinatra, and even the Beatles, but despised most female singers, who loathed her back. Speaking to Franklin, Wiley took a veiled swing at Peggy Lee, who used an oxygen tank offstage (a consequence of pneumonia) and quelled her nerves with Valium. “Today most of the girls are over fifty years old,” Wiley told Franklin. “They can hardly get up on the stage. For one thing they’ve gotta take oxygen or dope themselves up, and I don’t think that’s right. What they should be doing is being at home with their children. But of course most of their children are about thirty-five. Or they should be doing some volunteer work over at a hospital or something – in my opinion.”

Yet in 1971, she happily accepted an offer from producer Bill Borden to make one more album, Back Home Again, for his label Monmouth-Evergreen. A year later came her last stage appearance, at Carnegie Hall for the Newport Jazz Festival. Her attractively weathered voice raised goosebumps in viewers who thought they’d never see her in the flesh. True to form, however, Wiley infuriated her pianist – Teddy Wilson – by starting in the wrong key then glaring at him, so the audience would think it was his fault.

In 1975 she died of cancer. History has since granted her a respected place in the history of early pop-jazz. With nearly all her recordings available on CD, Lee Wiley won’t be forgotten any time soon.